Architect Dave Strachan takes a long-term view on design and building. He talks through his formula for sustainability.

Sustainable building involves designing a structural solution that meets desired living and occupancy needs whilst placing as light a load upon the planet as possible. Buildings which are designed to be comfortable in all seasons and have strong connections to their context and landscape will have longevity. They possess ‘an appropriateness of place’. If the building also evokes a positive emotional response, it will likely have a life that will extend to future generations.

Sustainable buildings can be evaluated in purely scientific terms by measuring their carbon footprint, energy efficiency and thermal performance.

But to fulfill the purpose of architecture, they must also uplift the human spirit. We need to feel the wind on our faces, the sun on our backs. We must be protected from the elements yet still feel connected — both to our environment and to the people with whom we share our lives. Sustainable architecture must reach beyond science.

In order to create a sustainable house design, the following four points should be considered within a cyclic design process.

Step one: the site

Analyse the proposed house site in detail with the help of specialist consultants, council records, aerial photography, geological maps, historic photographs and NIWA climate data.

Focus on these points:

-

Landforms and contours — research land stability, water courses and flood risks.

-

Building context — look at existing buildings and surrounding neighbourhood.

-

Vegetation — consider the risk of overshadowing, blocking or filtering of light.

-

Infrastructure and utilities — drainage, water supply, power and telephone/internet connection.

-

Local body regulations — zoning, bulk and location controls.

-

Legalities — title, covenant and easement issues.

-

Climate nature — prevailing winds, temperature fluctuations by season, monthly rainfall, sunshine hours and direction.

-

Atmosphere — dampness and humidity, salt-laden, geothermal, mean temperatures.

Step two: users

-

Analyse your family’s needs from your living environment.

-

How much space do you require?

-

Can certain spaces have multiple uses?

-

What is your budget?

-

What are your aspirations for the project?

-

Do you want your home to make a statement about sustainable living?

-

Are you focusing on short-term spend (lower initial cost leading to higher long-term running costs) or taking a longer-term view (higher initial cost then lower running costs)?

-

Apply Lifemark accessibility principles that enable occupants of all ages to remain in their homes rather than requiring specialist accommodation.

Step three: materials, finishes, structural system and construction

Use this checklist to properly analyse your options:

-

Research and select appropriate materials and finishes for both design and context.

-

Where fit for purpose, use natural materials to add a human quality to a building. For example: an oiled timber showing its varied grain, colour and smell or a locally quarried stone that is both durable but ‘of this place’.

-

Prefabrication in factory-controlled conditions is now preferred over traditional onsite building, particularly in New Zealand’s wet winters. This process has advantages in terms of speed, quality and cost.

Step four: applying the Sustainability Criteria Matrix*

In order to create a wholly sustainable home, your architect should apply as many of these 12 Sustainability Criteria Matrix principles as is feasible:

1. Minimise cardon dioxide emissions: Your building should be located in a way that minimises the environmental impact of the four CO2 generating elements associated with housing: transport, embodied energy, food production and operating energy. Urban buildings will perform best due to their proximity to public transport. However rural buildings have the best capacity to produce food on site. Good design in either case has the capacity to reduce operating energy and energy ‘embodied’ in the production of building materials and the construction process itself.

2. Minimise energy demand: Buildings should be designed to minimise their demand for energy. This means a high performance ‘thermal envelope’ is needed with high levels of insulation. This should incorporate selected single and double-glazed areas, accompanied by a substantial area of well-insulated material with high thermal mass properties such as dense concrete or masonry. This needs to be heated by the winter sun and shaded from the higher altitude summer sun to prevent excessive heat build-up and to enable the mass to provide summertime cooling.

3. Respond to climate: Buildings should be designed to respond to the climate specific to its region. They make the most effective use of the natural, renewable, non-polluting resources available — sun, water, earth and air.

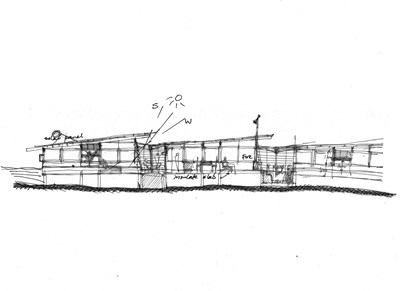

In the early part of the twentieth-century, American architect Louis Sullivan created the tenet ‘form follows function’. In creating sustainable architecture, perhaps it is better to use the notion of ‘form follows climate’. In simple terms, this means the site’s landform influences the building form, together with aspect and shelter.

Use of the ‘form follows climate’ design approach together with creation of a high performance thermal envelope are the most important design decisions to be made. Added to these is the need to integrate ‘active’ systems to assist building performance. These typically include solar water heating, photovoltaic and wind electricity generation, heat pumps, low-energy lighting and appliances.

4. Minimise resource use: Target minimal use of new resources in building construction and instead encourage use of recycled materials. New buildings need to be designed for flexibility of use. Any existing structures should be seen as a valuable resource capable of being adapted and retrofitted to meet changing needs and uses.

5. Reduce and recycle wastes: You should aim to reduce all waste and recycle what can be re-used or re-purposed. Recycling bins and composting areas are important waste management strategies.

6. Collect, conserve and recycle water: Water is becoming an increasingly important resource and should be collected, conserved and recycled.

7. Create a healthy indoor environment: The selection and treatment of materials to be used throughout the home should provide a healthy indoor environment for your family.

8. Select materials according to Life-cycle Analysis: You should choose building materials according to the key principles of Life-cycle Analysis — adaptability, suitability, recyclability and embodied energy.

9. Demonstrate sustainable systems: Sustainable buildings should enable their occupants — you and your family — to understand the principles of sustainable design by visibly demonstrating the systems used.

10. Provide an operational manual: When completed, your new sustainable home should come with a systems and maintenance manual that explains how to use your house and its embodied systems most effectively. This should contain advice on maintenance regimes, details of the construction team and other tradespeople involved, plus how and when to activate natural ventilation and sun-screening systems in different seasons.

11. Respect the vernacular: To remain true to sustainable building principles, any new building should respect local context and architectural ‘vernacular’. Regionally relevant construction methods and practices should also be employed. This is the opposite of using imported architectural styles. Tuscan villas are not an appropriate model for New Zealand’s climatic environment.

12. Create good architecture: Buildings must not only meet technical standards in materials and construction, but also human, social, aesthetic and contextual considerations. Both architecturally and as a living environment, they must equal ‘a good place to be’.

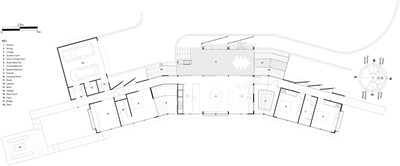

This article, by Dave Strachan of Strachan Group Architects, first appeared in Design Guide (issue 3). The featured project is the Owhanake Bay House, Waiheke Island, winner of a New Zealand Architecture Award in 2012.

This article, by Dave Strachan of Strachan Group Architects, first appeared in Design Guide (issue 3). The featured project is the Owhanake Bay House, Waiheke Island, winner of a New Zealand Architecture Award in 2012.

Photos: Patrick Reynolds

*The Sustainability Criteria Matrix was established by Dave Strachan as a key component of his thesis on Sustainable Architecture in 2000 and it has been developed by and informed the practice of SGA since.