Gold Medal interview: Pip Cheshire

2013 Gold Medallist Pip Cheshire talks surfing, the CIA and civic architecture with John Walsh.

John Walsh: Let’s start at the beginning, Pip – you’re from Christchurch, as were your parents.

Pip Cheshire: Yes, my sister and I, and both my parents, all went to the same primary school in Sumner. I grew up right on the waterfront. I’d roll over in bed, open my eyes and there were the waves, with the seaward Kaikouras poking out above the horizon.

Hence your maritime predilections?

I was always more at home in the water. I got scooped up by the Crippled Children’s Society, as it was then, and went to swimming classes every week. That started when I was about three. There were people who had no arms, no legs, who were taught to swim by a remarkable guy.

What had happened to you?

I was born with one leg – it was just random error. I lived a great sort of middle class life, right on the water’s edge. My father had been in the war, and when it was over he stayed in Britain and learnt how to make pipes – smoking pipes. When he came home he made a little factory in Sumner, with the help of his father, who was the local Borough Engineer. My father made pipes for six or seven years – about a quarter of a million of them.

How did the other kids at school react to your handicap?

I got alternatively looked after and beaten up. But I suspect that was partly because I was a bit of a prick. I had a ‘f…you’ attitude. Also, my dad had a factory and we lived in a big house on the waterfront so there was sort of a class thing. Sumner was split three ways. It had a state primary school, a Catholic primary school and a boarding school for deaf kids. The bay was just so divided. If you went down the wrong street on your bike you’d get pushed off or chased.

After primary school you went to Christ’s College?

And that didn’t help. On my last day at primary school a bunch of girls grabbed me and dragged me behind the dental clinic and beat the s… out of me.

Were you a day boy at Christ’s?

Yes, and that was a mission because I had to leave home at six in the morning, or earlier. If you were a ‘fag’ you had to catch the first bus into the Square, then bike to bloody college, and then clean the toilets – stuff like that, six days a week. It was part of character building. You spent six days a week in a three piece suit and went to chapel on Sunday, unless you lived more than five or six miles away. Then you could go to your local church instead. Sumner was about seven miles distant, so I had to go to the local church in my school uniform.

How did you do at Christ’s?

I really enjoyed it because it totally occupied you. I know some people got crushed by the school, but for me it was great. There was a lot of support and all sorts of challenges – I was able to play indoor basketball, for example. I found kindred spirits at the school and I feel I had a good liberal education. There were a lot of activities up until the Fifth or Sixth Form and then music took over and also I was surfing a lot. My family was living in town by then. I’d be picked up after school by these guys with major heads of hair and wild cars.

Why did you like surfing?

Because I could do it, and when I started nobody quite knew what it was. I remember in the Third Form having to explain what a surfboard was.

Again there was a good sense of ‘f… you’. People would see me catching a wave when they were paddling out, which was always a slightly daunting time before legropes because you know somebody’s going to fall off and you’re going to get a face full of surfboard, and then they’d see that I had one leg.

I liked that I could scoot circles round them. There aren’t many other sports where I could do that. It’s also a case of doing the thing you’re least suited to doing, isn’t it? All other things being equal I should be a stamp collector or something. But hypochondriacs become doctors and those of us who are spatially confused become architects. And people with one leg become surfers.

Christ’s College has an ensemble of strong buildings. Did the school’s architecture make an impression on you?

Yes, and it has strongly influenced the way I see space. There’s huge power in that idea of common open space with cloisters around to privatise the edge. There’s also solidity. That’s why I still look at the work of The Group and think, ‘What the hell are these flimsy little things?’

You have a Canterbury perspective on upper North Island architecture.

Absolutely. Let’s dig in here – let’s make some serious buildings. I mean, Maori did when they came ashore. They gouged every hillside in Northland. Now if you want to move anything more than a cubic metre you’ve got four years of resource consents to go through and yet the tangata whenua did these fantastic earthworks everywhere. That’s the spirit. There was a great continuum from the big pa sites to the Benmore dam, and we’ve lost that courage.

Between leaving school and leaving Christchurch what happened?

I went to Canterbury University and did a terrible degree, really. I was playing in a band, I was surfing. It took me about five years to get a degree. I did political science and worked part-time in a factory making the insides of fridges. One day I brought Trevor Richards of HART [Halt All Racist Tours] into the factory at lunchtime to talk about why the All Blacks shouldn’t go to South Africa and the bosses shifted me out to another place where I fabricated Perspex.

My dad, after he had finished with the pipes, had a factory making safety equipment, including motorcycle helmets. About the day I left university his fibreglass supplier had an accident. I said, ‘I can do that’, because I’d done some fibreglassing in Australia and you could set up in business for nothing. You’d buy a drum of resin for $200 and a bunch of fibreglass cloth and some paintbrushes and you were pretty much in business. My dad paid me cash so I had a cash flow. I could never work for him because we used to argue. We spent a decade arguing about the Vietnam War.

You could make things with your hands – you’re not a klutz.

I am, actually. That’s the irony, but my ego is bigger than my ability and so I’ll put myself in the position of saying, ‘Yeah, I can do that’. So I had this little factory with a dozen people making hundreds of helmets in the days before they could be imported. I was also fiddling about with other stuff. I was setting Marimekko material in resin and making tabletops and mirror frames and selling them to a contemporary furniture shop in Christchurch.

You were a little capitalist.

I’ve always been one of those. I’d employed people to make stuff when I was at university.

You were running the factory and a business. What triggered the change in your life?

The factory was just something to do. I was confused and not sure what I was up to. I was living in a big apartment, full of interesting people. Christchurch has always had pools of interesting people. When I was growing up in Sumner my parents would go to parties which were wild, even by today’s standards, with people like the architect Paul Pascoe. His house was radical. Today it looks tame, but not in comparison with the norms of the time.

Anyway, my flat was falling apart and everyone was going their own way. The last hurrah was going to be an overland trip from Anchorage to Terra del Fuego by Cadillac, but then the Allende government in Chile was overthrown. All of us had associations with the left of one sort or another, and so a third of the trip was suddenly no go. We wouldn’t have got visas.

You would have been on someone’s radar?

I think so. I was on Canta, the student paper, and I’d go and interview someone like the police superintendent and he’d know everything about me.

I was also president of the Politics Society and during the Vietnam War these stooges from the CIA would come in vast great limos with Old Glory fluttering and take me out to lunch and try and soften me up. It could be scary in those days – 1968, ’69, ’70.

Printing presses had to be licensed. There was a guy who was known as Christopher Robin – I didn’t know his real name – who had a printing press which would be pulled apart every night and carried to different parts of the city. I helped print a broadsheet for another guy, who should remain nameless, and moved his Gestetner around. The paradox of the times was that you could get on the phone at night and ring Muldoon or one of his ministers. You’d say, ‘It’s Canta here’, and get straight through and talk for half an hour.

How did you decide on architecture?

As my grandmother reminded me, after I’d completed my first term at Architecture School, The Press had once interviewed me when I was young and I’d said I wanted to be an architect when I left school. So there was always something there. I always drew a bit, and I designed letterheads for my father and graphics for his business. I might have been frigging around, but I was definitely looking for something. I just didn’t know what.

I was playing chess with a flatmate who was teaching classes in the Liberal Arts block at Ilam, and just then it came on the TV news that it had got a National Award for architecture. I said, ‘We should be able to do better than that,’ and he said, ‘Well, why don’t you?’ Pretty much the next day I came up to the Auckland School of Architecture and had to sit outside the dean’s office for about an hour for an interview.

The dean was Allan Wild. What did he make of you?

They were open to odd bods, I guess. When it came time to formally apply, I sent up a two inches thick of wad of stuff with Paul Pascoe’s great reference on top: ‘I’ve known Pip since he was born – he should be able to do anything he wants to do’.

I started at the School in 1976. Mal Bartleet, who became a very close friend, was there, and Lawrence Sumich, and Mark Wigley. Mark and Mal and I were addicted to pinball in the fourth year. We used to travel around the city playing pinball – maybe that’s where Mark’s ideas of randomness and deconstruction had their genesis. Richard Priest was in the same year, and Pete Bossley, Amanda Reynolds was a couple of years ahead and Rewi Thompson and Noel Lane a year or so back.

We had Claude Megson who drove me mad with his malapropisms, his sexism and his mis-quotations, but he did give great lectures. He had a course called Architectural Aesthetics where he would play Mozart or Beethoven at enormous volume. There’d be two slide projectors changing slides every half second – he was a beautiful photographer. He would alternate that with a lecture about the Ancients. In one class I said, ‘Claude, all these great people you’re talking about, they’re all blokes and for every free man who’s writing poetry or making great Doric columns there are a thousand bloody slaves living in abject misery and being put to death’.

One of the students launched out of the front row and put his hands round my throat and said, ‘What the f… is wrong with you? I’m sick of you’. It was pretty lively.

David Mitchell was teaching at the School, and Mike Austin and Kerry Morrow. Dick Toy was there, and John Goldwater, who was a gentle, intelligent, sensitive man. There was John Dickson, who was very strong but we used to argue like fury. But despite these figures, the School was in the grip of what I call a muddy humanism. The intellectual activity of those like Dickson was not foregrounded at all. The School changed a great deal when Ross Jenner arrived. Ross was unashamedly intellectual and brought a sense of rigour to the School.

Do you think the ‘muddy humanism’ of New Zealand architecture betrayed a discomfort with intellectualism?

Certainly when Pete Bossley and I got underway New Zealand architecture was in the grip of the self-effacing, jocular approach epitomised by Ian Athfield and Roger Walker. Ath is wonderful talking about society and the built environment – absolutely wonderful – but it’s hard to get him to talk seriously about his own buildings. David Mitchell, too, has an armour of throw-away lines, though he is our best commentator.

Are architects fearful of being thought pretentious?

We’re in a society that is quite tough. It’s not just architects – look at the way we treat teachers.

When you graduated what was going on? Post-modernism?

Just about, at least in the magazines and the books – Venturi’s Learning from Las Vegas and stuff like that. But, no, most of the local Auckland houses were still tanalised timber sort of things.

How did you start out in practice?

In my last year at the School I did a restaurant in Auckland called The Melba. It was probably the first Auckland restaurant to make a big deal out of the bar. I handed my thesis in and then raced up to a tin shed in Jervois Road, a place that had been rented as a kind of studio by a bunch of students – Amanda Reynolds and Kent Dadson and a few others, eventually just Amanda working by herself, doing house alterations. Mal Bartleet arrived an hour after me and hot-wired a phone line from a neighbouring line, and we got a print machine and stuff. Pete [Bossley] turned up a few months later after escaping from the Ministry of Works. He arrived and called himself Roy L. Doulton.

In a contemporary film about those early days you all talk about having a street-front practice where people from the neighbourhood can drop in. You weren’t going to be like those uptight downtown architects. You were going to do architecture for the people.

That’s right. Lovely irony, isn’t it? We soon shifted further down Jervois Road and started to get employees – Rick Pearson was the first – and then we bought a Freemans Bay warehouse. We called ourselves Artifice – there was Mal, Pete, Rick, Tim Hooson and Greg Boyden. It was a sort of collective, which got in the way when we started to get bigger jobs – we had to negotiate over staff every day. I didn’t think it was going to go anywhere, and nor did Pete. We wanted to get serious about architecture and so he and I formed Bossley Cheshire, which lasted a couple of years.

I got a lot of noise out of The Melba, so I got some houses to do, then more houses and it just grew from that. We would take every opportunity to write and talk about our work. A really important figure for me was the design teacher Nannette Cameron, who ran an interior design course out at Pakuranga. She got me out to talk a number of times and I got a lot of work from that.

What happened to Bossley Cheshire?

We won a competition run by JASMaD to do a subdivision scheme. The project didn’t go ahead but not long after that JASMaD rang up and said, ‘How about we do some work together?’ We went over and they said, ‘Actually, what we want to do is have a merger’. We started talking – it took about a year.

Was the attraction for you and Pete the opportunity to work on larger projects?

That’s right, yeah.

JASMaD was a big practice, in New Zealand terms. What did you and Pete make of its culture?

We were a bit challenged by it, really. When we finally decided everything and were sitting around the table I asked what the new practice would be called. ‘JASMaD,’ they said. Rem Koolhaas was becoming the man of the moment, so I said, ‘Let’s call it something like Office for Metropolitan Architecture’. They were outraged – ‘We’ve just spent $2,000 on reprinting all our stationery’ – and it fell apart. A month later JASMaD rang up and said we’d better get back together.

I hadn’t realised what a confederation of practices JASMaD was, and at first it was difficult, but winning Te Papa made a difference. Almost immediately after we’d got together the competition was announced, and Pete and I and Ivan [Mercep] agreed to dive into it, and David Mitchell too. David soon left – ‘There’s too many bloody designers here,’ he said. And when the competition was won, I thought three designers were still too many, so I exited too.

Why was it you who left the Te Papa design team?

Pete had driven it harder than I had, and I always think everyone is better at doing things than I am, so I was quite easy about leaving. Ivan was the architect of Te Papa, if you read ‘architect’ in a broader sense way, as somebody who gathers together political will and budget and process to make a building, though of course Pete drove the design.

There have been suggestions that Wellington could have had a Frank Gehry building, before Gehry did the Guggenheim Bilbao.

I think we were saved, really. I’ve visited a number of Gehry’s buildings, and I think they do a great thing for a city because of their outside appearance, but they’re not very successful as art galleries.

What did you work on at JASMAX?

I’d brought the Congreve House with me – it was designed at Bossley Cheshire but documented at JASMAX. Some of the partners said, ‘This is a great risk to us, you know – it has no eaves’. JASMaD had been doing big flyaway eaves – everything was like a suburban house.

I was also desperately trying to update the practice, and get it into computing. I spent a lot of time on that – I was a bit of a geek. We had a computer manager who wouldn’t let me have a log-in, and so I would go in at night and try to hack in. In the end it got really desperate and I said, ‘I’ve bloody mortgaged my house to pay shares for this thing – I want a log-in’, and the guy said no. So that weekend a friend professionally hacked into the whole system and mapped everything.

The Congreve House – what were you trying to do there?

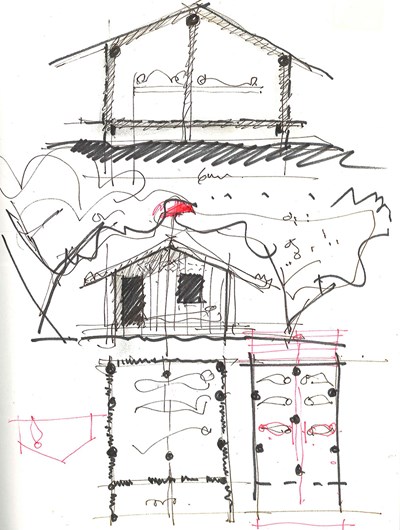

I wanted to make a solid building. I wanted to come ashore, unpack the cases, put my heel in the ground. Don Clark was a great motif for me – you know, those photographs of his heel thudding into Eden Park, before he placed a goal kick. I wanted to design a place to stand. And I had great clients. I’d already done a lot of work with the Congreves. We looked at a range of properties. We were interested in the relationship with Rangitoto (see sketch, above). Erika Congreve wrote me a brief that was eight lines – four bedrooms, a study, living room, dining room. We had the site, and I said I’d hole up at our bach near Matapouri Bay and meet her in a few days with some sketches. When I got back to my drawing board, there was a note from Erika: ‘I don’t think you understand. The house will cost what it takes to build and be built when it’s ready to be built’.

That’s quite a thing to tell an architect.

Then Erika said it was to be a world-standard house, and I thought, ‘God, this is very serious’. I started designing the house, and on Sunday nights we’d drink a bottle of wine and talk about buildings and then they’d go for trips and visit the buildings.

I was interested in a solid house and a place that had a particular relationship with Rangitoto. I was also interested in the relationship between the eye and the island, and the nature of bigness. Then I got interested in aural qualities. In what way does a big house sound different from a small house? And then there was the Congreves’ collection of paintings – how would one show those? Logic would say a white-walled house but I was interested in how materials might be dealt with. I was concerned not with a material honesty, whatever that means, but in a kind of rawness – the raw and the cooked, as Lévi-Strauss put it – the finely engineered against the robust.

I was interested, too, in the idea that you might visit the place and it might seem simple and facile, but if one was to draw a plan of it you’d be sort of dumbfounded. You’d realise there were some parts of the house that hadn’t been revealed to you. It was an exploration of bigness, really.

When you eventually left JASMAX it was via the Britomart project, wasn’t it?

I got a call one day when I was still at JASMAX – ‘You don’t know me, I’m Peter Cooper.’ I said the best thing I’ve ever said in my life: ‘I know you, you’re the surfer from Newport Beach’, and he said, ‘Yes, and I’d like to talk to you about some land I’ve got’. I went to see him and we just talked about surfboards for an hour and I came home and realised we hadn’t talked about housing. So I started doing the house at Clifton Road, and that was very difficult planning. But it’s a good house, I reckon. That was done at JASMAX.

I imagine that as both you and Peter Cooper are determined characters, the relationship has had its challenging moments.

Yeah, but I’ve made some good buildings for him. They’re not compromised, but they are much more negotiated than other places I’ve worked on. As for differences between an architect and a client, I would strongly defend being argumentative and difficult because as the project proceeds I’m confident I know the client’s best interests. At the beginning of a project I’m really loose. I say to the client, ‘Whatever you want – you tell me’. And then it becomes, ‘Wait a minute – this is what we’re on about here’. I once had a client who screamed down the phone at me – ‘You bastard, the only thing that stops me firing you forever is I know you’re arguing for my best interests’.

You’ve done a number of projects in the public or civic realm. There’s the Bruce Mason Theatre and Q Theatre, for example, and the Auckland University Marine Laboratory and your work at Britomart. You must like operating in that world.

I enjoy this type of work because it has more complex issues. The role of the architect on these projects, as a kind of shape maker, is generally accepted. All of the business about what things look like – by and large you’re left to your own devices on these things, although there’s always a moment of reckoning. But you find yourself involved in much more complex areas, like politicking to get access to a site or to help fundraising or to generate the political will to prevail through the resource consent process. I enjoy that.

If you don’t engage on this level you end up designing the kitchen, and how many kitchens can you do in a lifetime? If you’re serious about shaping the city you’re not going to do it by designing individual buildings. You’re going to do it by influencing the political or strategic context in which decisions are made.

When you look at Auckland are you more optimistic than you were a decade ago?

Yes, I think it’s really exciting. I think we’ve reached a kind of critical mass, a tipping point where the city is big enough to have its own internal expectations and its own reasons for growth and development. It has sensed that it’s part of the globe. People have higher expectations, especially of hospitality and residential architecture. Our commercial and institutional buildings lag behind.

Let’s talk about your growing practice.

Our practice.

What do you mean?

I’m now fighting the ambitions of my son, Nat, you know. All these people come up to me and say, ‘Oh, so you’re retiring, are you?’

Oedipal issues aside, are you happy with the work your practice is now doing?

You mean the quality of the work or the type of work? On both fronts, I think we’re doing really strong work and I’m much clearer now. I’m more confident. I don’t defer to others quite as much as I used to.

What is your architectural direction now?

I really enjoyed doing Q Theatre and I enjoyed doing the Leigh Marine Centre. They were very different in terms of client and brief but I enjoyed the scale of things. I think there’s a common strand running through the work, even though the projects vary widely in terms of appearance. I’m interested in a kind of clarity, a paring back. That, coupled with an acknowledgement that there are no singular answers anymore.

I have no truck with revisited modernism, the kind of neo-modernism that’s going around. We’ve lost the modernist social agenda, so modernism has been disempowered. It has become a style thing. I’m interested in clarity, which can coexist with great complexity.

I’ve always felt the exterior appearance of a building is a sort of devil’s work. There’s corruption in there, a fetishising of one sense over the others and over the intellectual raison d’être for a project. I remember David Mitchell saying he hated elevations – he always left them to the end, and I have a lot of empathy with that view.

Is there a building you’d like to do?

I would be more interested in somebody who didn’t come with a prescribed list of things. An institutional or civic building would be great. Breathing some life into the St James Theatre in Auckland would be fantastic. But I don’t really have a wellspring of houses or buildings waiting to get out. My buildings have grown out of relationships, and in the absence of a relationship there is no work. There is nothing.

Would you like to work in Christchurch?

Christchurch is unfinished business in many ways, but given the way it’s shaping up as a kind of tilt-slab town I’m not sure I’d want to work down there. I’ve been down there a number of times since the ‘quakes, and when I looked around the middle of Christchurch I couldn’t figure out where the city should be. I think we’ve raced through to rebuilding without conceptualising what the town is about, which is a classic Kiwi response. You used to be able to understand Christchurch. It had the cathedral in the middle of it. It had a diagonal line that went out to the port through a hole in the wall of the Port Hills, and another diagonal line that went out to the hinterland where the sheep were. You had to wade through the suburbs for a while but that’s what Christchurch was about. Even before the earthquakes I wondered what Christchurch was becoming. It was losing or blocking the traditional pathways, and once you lose them, what is a city about?

After the earthquakes I thought Christchurch needed to be seriously reconceptualised. How do you avoid becoming one of those anonymous new towns? I tried to promote a gathering of people, the best of the brightest who had left, the Peter Coopers of Christchurch – and there are a lot of them, in all sorts of realms. In the absence of a profound reconceptualisation I fear we’re just going to build a shallow version of what the city once was. I would, though, like to do something in Sumner, my battered home town.

You seem to have a very happy family life which must be a great enabler of your career.

Yes, I am a lucky and happy man. I work closely with Nat, talked politics with Finn, the diplomat, when he was our man in the Solomon Islands and have been a roadie for Hal the tattooist when he was thrashing out a storm at the Kings Arms. We are an extremely close family – my wife Aileen teaches at Unitec and has a counselling practice and still finds time to be a very wise and gentle woman at the centre of things.

I’ve also had great collaborations with people. The collaboration on the Congreve House with Kendon McGrail was really important, I think for both of us. Working with Kendon and Stephen Rendell on Peter Cooper’s Auckland house, and with Stephen on Peter Cooper’s Mountain Landing house up north, and with Richard Naish and with Christina van Bohemen on another two houses, entailed close and strong relationships. My relationships are either really intense or they kind of bounce off, and that’s with clients as well as people I’m working with. I’ve had failures. I’ve been fired by people and I’ve fired people and there have been some unsatisfactory ends to things. So those successful collaborations have been really important.

You have mentored many architects over the years. Is that part of your role now?

Probably less so now than in the past. Now I’m much more autocratic. Somebody said I make architects more than architecture, which I thought was interesting. I think the empowerment of people is probably the best thing you can do. One way of reading architecture is that we take a bit of luxury and move it from one side of the table to the other, and I get deeply embarrassed when I meet people who are nurses or something really critical. I think teaching is a really important thing, although teaching to beget more movers of luxury I’m not sure about.

For someone with a liberal political sensibility there must be a certain ambivalence about servicing the affluent.

I deal with some very wealthy people so, yeah, it is a bit of a paradox for me. But I have some pro bono projects running all the time. For example, I’m working for a crew on Great Barrier who are trying to get some pensioner housing together because when people get old on the island they have to come back to the mainland, and then they only live for another six months.

You have a Protestant work ethic, don’t you?

F… yeah. Also, because I was so dim and lost so much time in the 1960s, I’m on a catch-up. For example, this is a fiction catch-up year. I read American contemporary literature when I was at university but I’ve read very little other literature. There are a lot of holes to fill. So this year I’ve read Anna Karenina, Moby Dick and The Ugly American, and now I’m on Katherine Mansfield’s short stories. Heart of Darkness – that’s another one. I read Conrad’s Lord Jim years ago but Heart of Darkness is something else. Yeah, it’s a big year for reading novels for me.

What about writing? That has always been important to you, hasn’t it?

Yes, but I am sort of a short order cook, you know, ‘One book review, 1000 words, sunny side up, by 5.15’. There is a project welling up inside. I enjoy getting a result in a day or so and little chance of being sued – a bit like cooking and not like architecture.

All things considered, I get the feeling that your decision to go into architecture was a good one.

Somewhere I think I said I’m really sorry for people who don’t do architecture because it seems such a great thing – you can draw, talk, put a hard hat on and be a person of mud and clay. Yeah, I think architecture is a wonderful thing to do.

This interview first appeared in the 2013 NZIA Gold Medal publication.