Journey to the Homeland

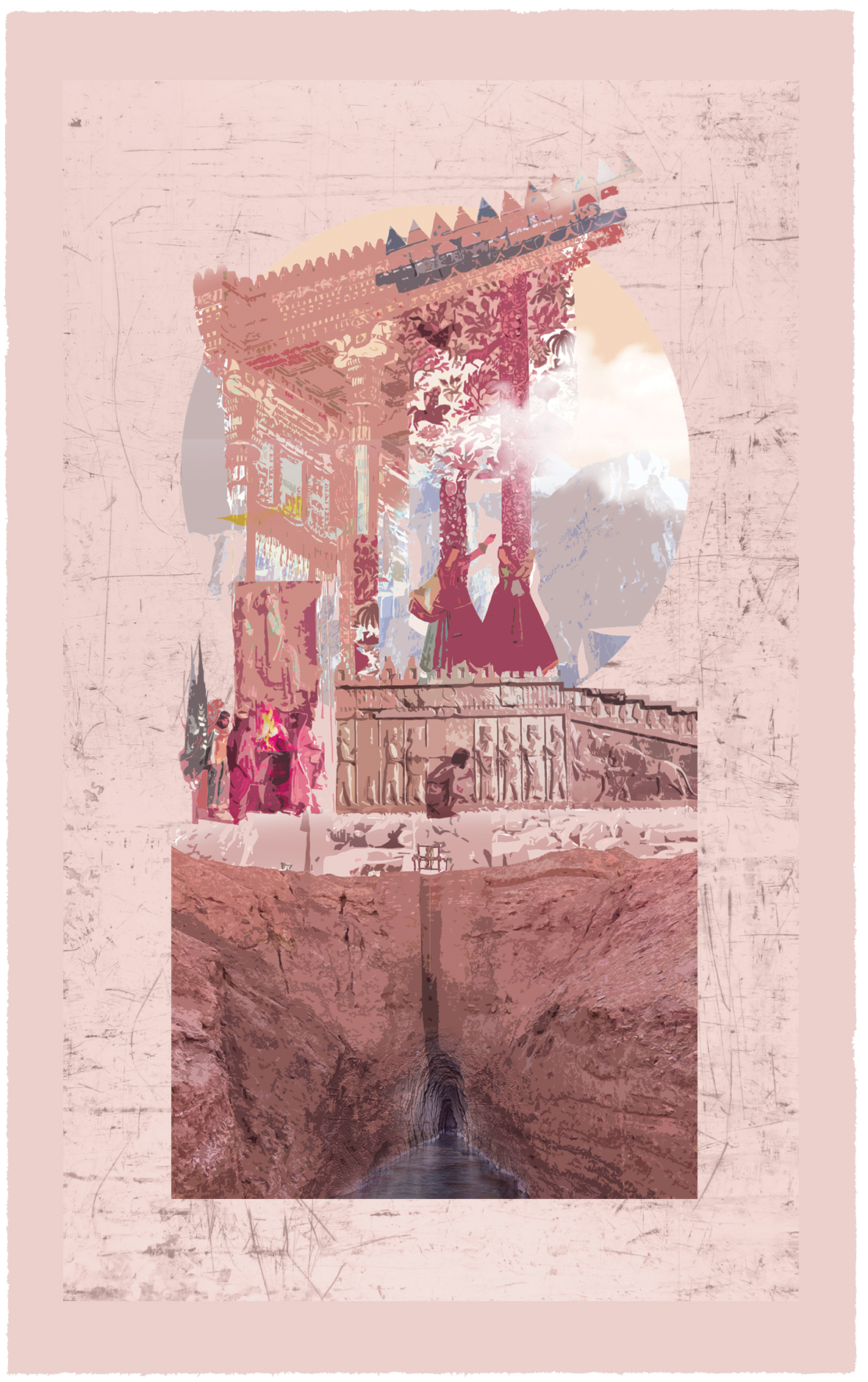

Architecture student Delnaz Patrawala takes us on an evocative journey back in time to Ancient Iran, the homeland of her Zoroastrian ancestors.

The sands remember the footprints of our ancestors as they journeyed from homeland to new horizons.

Moving from one’s homeland is a trek across time and space, to a new condition, a new way of life. The new surroundings are an assault on the senses – everything is unfamiliar. The sound of water as it hits the roof is unfamiliar, the way people talk is unfamiliar, the smell of a freshly mowed lawn is unfamiliar. Migration is not just relocation but implies a physical disconnection from the homeland and its culture. There is an undeniable feeling of duality and a conflict of the cultures within oneself and the influences at work in our physical surroundings. As time passes, the memories of the homeland fade; now only dust sits on the old rugs in storage, which I once laid on by the fire.

Ancient Iran – a civilisation of 2500 years – was once the home of my ancestors. It has seen many waves of oppression, emigration and heartbreaking destruction. To see it restored in my lifetime is a distant dream. Having spent much of my childhood in New Zealand, I consider it home. But there is no space, no footprint here in New Zealand, that gives me the necessary means of connecting with my ancestral homeland. I can’t help but feel there is a history and a culture for me to interpret and translate.

The books stacked in the corner of my room are glossy paper maps to a lost world of underground canals, richly layered gardens, tombs pressed into mountains, grand terraced palaces, and sacred fires – today a pile of ruin. Scouring the pages, I am borne across the ocean with a shovel, to unearth the living layers of antiquity, all in a quest to illuminate my knowledge of who I am and what I am a part of – a quest for my roots.

---

I am lowered down a well; a single frayed rope cinches my waist. Freshly bored earth envelops me on all sides, sliding between my fingers. The air is dense in the qanat (tunnel). The flame of my tallow burner flickers as I descend into the gallery. Clothed in oiled calf leather, I wade through the horizontal gallery (about 120cm high and 80cm wide), crouched 30 metres below the Earth’s surface. The sound of the world above ceases and only echoing waters permeate these underground vessels. Pickaxe in hand, I pry open the earth’s walls, lengthening the qanat until the hidden mountain waters reach my village.

At home, the water flows into the basement, a cool breeze. Coursing through the veins of the desert, it is the lifeblood of my people, the cornerstone of our civilisation. Here in the arid lands, water is scarce; the Zagros and Elbruz mountain chain prevents rain clouds passing into the region. The steady flow turns a motor, spinning two stone slabs, grinding wheat grains into flour.

Further downstream, past my village, lies a pairi-daeza (an enclosed paradise garden), an oasis in the parched sands. A carpet of wild flowers grows amid the fountains. Cultivated from barren land, it is a symbol of the king’s ability to bring symmetry and order out of the disorderly landscape – a reflection of his kingdom. Manifold and moving, the garden is a city within itself; a hunting preserve, a pleasure garden, the local bazaar, the king’s seasonal residence. It is a container of culture. I go to the garden’s bazaar to buy saffron, dates, rice and pomegranates.

In the distance I see the Naqsh-e-Rostam, a rocky mountain face with four punctures. These are the tombs of our Shahs, raised high above the sacred Zamin, so as not to contaminate it. You see, the Earth is our mother. Against the aggressive desert winds, she is piled high on all four sides, sheltering life within – her body, her womb, an enclosure nourishing a paradise, a garden. Moulded by the hands of her children, she is turned to clay. Worn by the winds, she seeps back into the earth from whence she came.

Back home after the day’s events, I tend to the hearth fire. It lives on for as long as the man of the house is alive. The atar is vitality, warmth, protection and transformation. It is sacred, a symbol of divine presence in our homes. I feel the heat sink into my skin. Outside, the chahar taqi, with its four arches and dome, houses another fire. Here, in the presence of nature and under the watchful eye of the sky, we pray.

---

“What is transmitted… from one generation to the next, in terms of memory today, is not a whole story, but mere fragments.” [1]

Ancient Iran – an imagined homeland, assembled by way of tiny fragments. Torn from the pages of the books, reclaimed and recomposed in the mind. When we describe a surrounding we aren’t physically present in, we are describing our memories, images and impressions of that place. Imagination fills the voids in memory. I have only pulled at the loose threads of the old rug in storage.

I know now that the homeland has less to do with geographical boundaries; instead it is an invisible thread of belonging to a culture and a community. In today’s interconnected world, we are tethered to so many invisible threads; they affirm our sense of identity. We carry them with us, as you would carry your precious belongings in a suitcase. Who are you? What is your story?

We are all, in some ways, communities adrift.

I have always felt drawn to visit Iran. But the Iran that my ancestors knew is no more. Time and space have created a double filter between the country and its diasporas. By spinning threads of attachment across time and space, we have woven a passage of memory.

The books are my maps and from my armchair I voyage to my homeland. I am transported through compelling images and stories. Evocations of an ancient way of life are made palpable. Having never travelled to my homeland, I can only imagine.

As I flick through the pages in my books, I am reminded of Salman Rushdie’s words: “It’s my present that is foreign… the past is home, albeit a lost home in a lost city in the mists of a lost time.” [2]

I try to walk in the footprints of my forefathers, to honour and understand my cultural heritage. I see the importance of diversity in our surroundings, our built environment, in forging those connections. Transcultural spaces become vessels in which to echo our stories, to unearth and remember our forgotten histories. Museums, art galleries and even gardens are richly layered, multi-sensory settings that transport us to new worlds. Here time slows and life stills, long enough for us to listen, to share in the story.

Even though I am a Kiwi, I am also Zoroastrian. From my home in New Zealand, I am embracing the duality of cultures within me.

---

I climb the monumental stairs of the ancient citadel; stone reliefs of my ancestors line the terrace walls. Row upon row of mighty stone columns with bull-headed capitals assemble, imitating the guards. The hypostyle hall, a myriad of columns. From this vantage point I look out towards the fire altars, my village, its gardens, the craters of the qanats. As the sun sheds its last light and disappears behind the mountains, I return home. Eventually, we all must return home.

1. Bilal, Melissa, ‘Longing for home at home: Armenians in Istanbul.’ In Diaspora and Memory: Figures of Displacement in Contemporary Literature, Arts and Politics, 55-66. The Netherlands: BRILL, 2006.

2. Rushdie, Salman. ‘Imaginary Homelands’. In Imaginary Homelands: essays and criticism 1981-1991, 9-21. London: Granta in association with Penguin, 1991.

Illustration by Delnaz Patrawala. This essay is available in 10 Stories: Writing about architecture / 6. Purchase your copy from our shop.